One common aspect of Chinese character learning is the relatively high prevalence of homographs. Homographs refer to a single character that has several meanings in different word contexts. Sometimes, those different meanings are even associated with different pronunciations. This can happen in other languages too. For example, in English, refuse can mean either to say you will not do something (a verb) or garbage (noun). However, in Chinese, homographs are much more common than in some other languages.

Homograph awareness is particular important for children learning to read in Chinese. If a child lacks awareness that a single character may have different meanings in different words or contexts, he or she may have difficulties in understanding a novel word containing that character and may even pronounce it incorrectly in some instances. For example, when ‘中’ is read as [zhōng in Mandarin;zung1 in Cantonese],it always means ‘ middle or in the middle’.

When ‘中’ is read as [zhòng in Mandarin;zung3 in Cantonese], its meaning is ‘ get, have, obtain.’ Therefore, a child who has learned 中 in the word “中間”(middle) may be confused when encountering it in 中獎(win a lottery)/中毒(be poisoned); she or he will likely pronounce it incorrectly in this context as well. Children’s homograph awareness occurs and develops when they encounter varied vocabulary words sharing the same character. They first understand the meaning of the whole words that contain the character that is a homograph and then go further to analyze and to memorize the meaning of that single character in context.

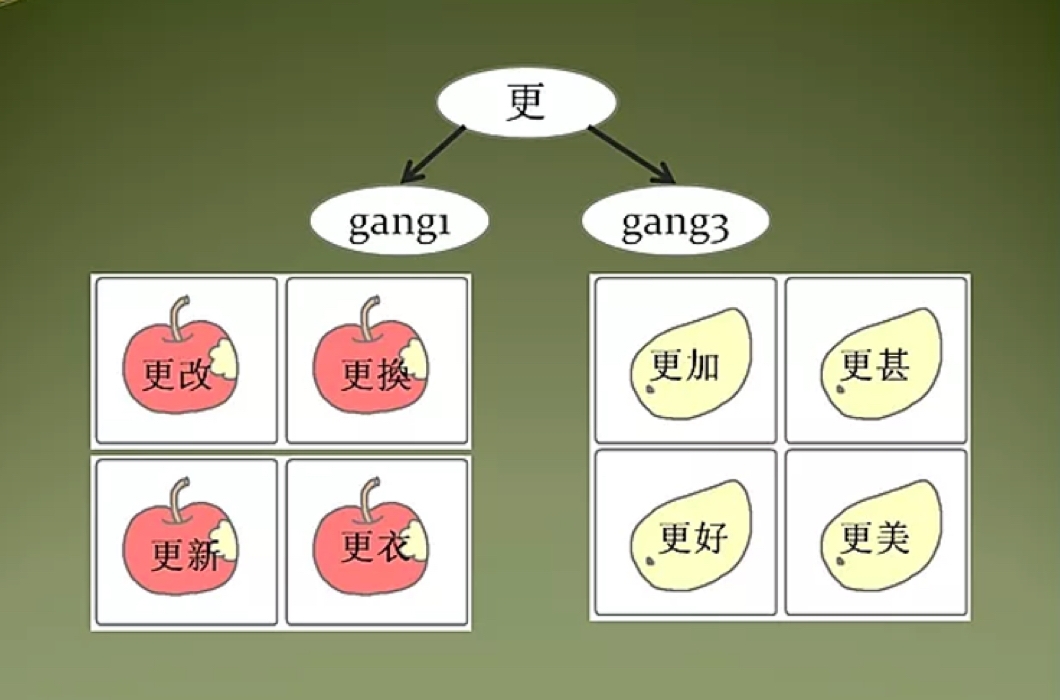

Parents and teachers can explicitly point out the phenomenon of homographs to children, with examples, to promote children’s early development of homograph awareness. Once children realize a character does not necessarily always have only a single meaning, parents and teachers can further make use of this discovery to help children to learn novel words more efficiently. Parents and teachers can present children with a few words sharing the same character and then ask children to group them by different meanings and/or pronunciations. Via this type of practice, children can gain a clear idea of which pronunciation is associated with which meaning, and which group of words is related to that meaning. For illustrations, there is one figure demonstation as shown above. And there are more game demonstrations in simplified Chinese on https://scratch.mit.edu/studios/1046570/. You can make your own set of cards in traditional Chinese instead if needed. As you plan for teaching,make two sets, one for learning and one for a game. The game set can follow my examples. However, for the set for learning, one can use different colors or different objects to indicate words groups, to make it easier and more obvious for children to read and to differentiate. It is also important for parents and teachers to remind children that not all homographs have different pronunciations in different contexts. Otherwise, children may infer that homographs with the same sound have the same meaning by mistake. For example, the character 明 in 明天(tomorrow)and 明亮(brightness)has the same pronunciation [míng in Mandarin;ming4 in Cantonese], despite the difference in meaning in the two contexts.

Because of the existence of homographs, in some instances, learning one character that carries multiple meanings might still help children to learn a large number of words. Homograph tasks may be more difficult than homophone tasks, given the fact that children have to access deeper meanings of the words in a homograph identification exercise. Therefore, it is likely that homograph awareness develops at older ages than does homophone awareness, and its influence on reading may also continue to higher grades.

There are some examples in Chinese

快樂[faai3 lok6]音樂[jam1 ngok6]

衣服 [ji1 fuk6] 服從 [fuk6 cung4] 說服 [seoi3 fuk6]

說話[syut3 waa6] 學說[hok6 syut3] 說服 [seoi3 fuk6]

道理[dou6 lei5] 道路[dou6 lou6] 知道[zi1 dou3] 道別[dou6 bit6]

中文[zung1 man1] 中間 [zung1 gaan1] 中獎[zung3 zoeng2] 中毒[zung3 duk6]

明天[ming4 tin1] 明亮[ming4 loeng6] 失明[sat1 ming4] 說明[syut3 ming4] 明白[ming4 baak6]

長度[coeng4 dou6] 長久[coeng4 gau2] 特長[dak2 coeng4] 成長[sing4 zoeng2] 長輩[zoeng2 bui3 ]

好人[hou2 jan4] 友好[jau5 hou2] 好多[hou2 do1] 好奇[hou3 kei4] 喜好[hei2 hou3] 好學[hou3 hok6]

This article was written by our guest blogger Dr. Mo Jianhong. Dr. Mo is currently a part-time research assistant in the Life Span Development Laboratory of The Chinese University of Hong Kong.